From Journalist to Water Carrier: Starting From Zero

Musab Mohamed Ali

*Originally published in Atar Magazine

In times of war and violent upheaval, it’s not just cities that fall — names, titles, and definitions collapse as well, stripping away the very identities that once gave people shape and meaning. In Sudan, since the outbreak of war, the greatest loss hasn’t been of land or borders, but of meaning itself — the meaning that once made a doctor a doctor, an engineer an engineer, a teacher a teacher.

With the state’s collapse and its institutions disintegrating, people are left confronting profound loss — not just hunger or displacement, but the erosion of professional identity, that bond between self, time, and society.

Sudan’s history is rich with political turbulence, with regimes rising and falling. But what we face today goes beyond politics. It’s a full-scale breakdown of meaning. A profession is no longer an extension of one’s identity — it becomes a heavy memory hidden behind a simple and jarring question: “What did you used to do?”

Yet despite this collapse, Sudanese people are not passive victims of defeat. On the edge of despair, many have rebuilt themselves through makeshift, painful means. New professions have emerged from nothing. Alternative identities have formed, not based on status, but on endurance and resilience.

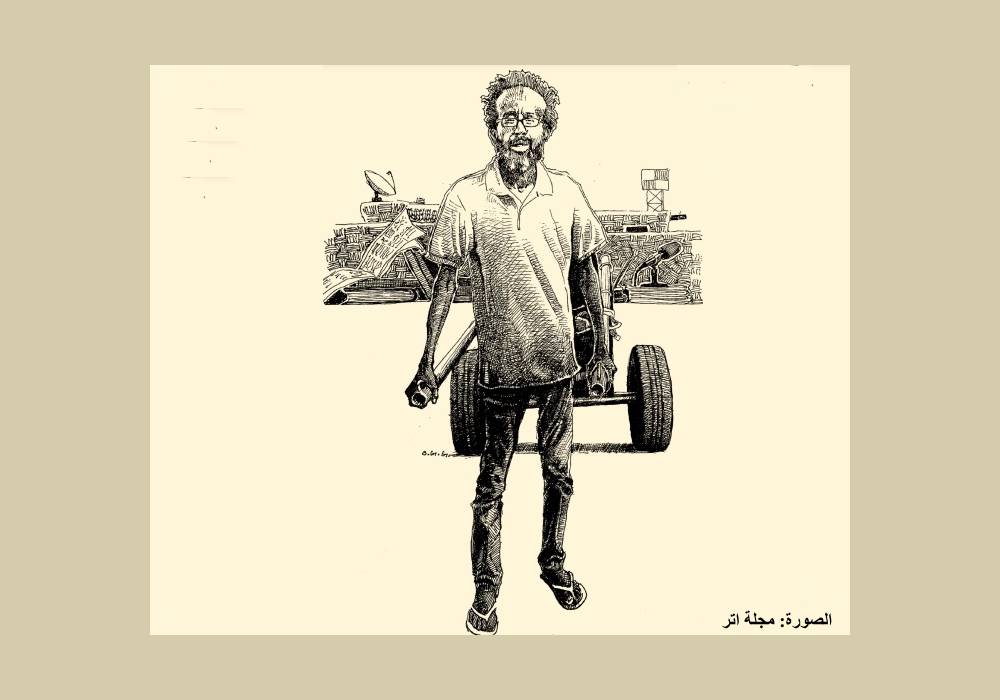

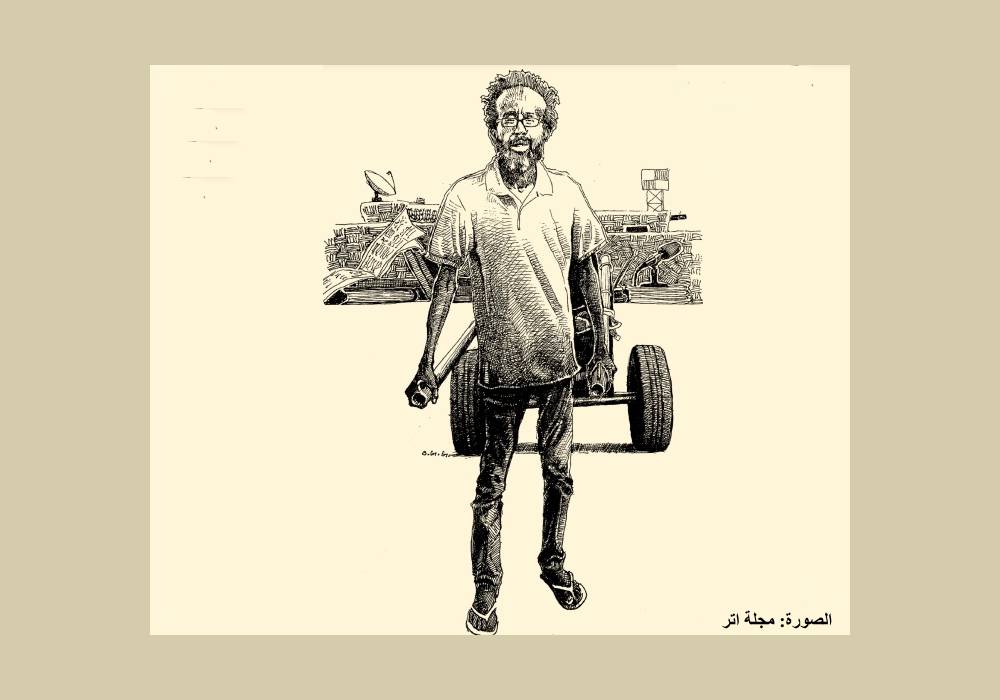

In East Nile, where life wilts under the long drought of war like trees under a blazing sun, a man walks with steady steps, delivering water. He moves past dusty homes, knocks quietly, offers a brief smile, and continues on.

Few know that this man, now simply known as “Masa the Water Guy,” was once “Professor Khalid Masa,” one of Sudan’s most prominent journalists. He had mastered the craft of news writing, discourse analysis, and reading between the lines. In newsrooms now abandoned, his fingers typed, his eyes observed, and his mind constantly pursued the eternal question: truth.

But war, as always, asks no permission — and preserves no dignity, not even that of a profession. When Khartoum descended into ruin, journalism was among the first casualties. Newspapers became a risk, opinion pieces became criminal charges, and access to printing presses was cut off. As Masa puts it, “In wartime, journalism was born — and truth died with it.”

At that point, he was forced to rebuild his life from zero — or even less. No savings, no pension, no safety net. Just his body, his social network, and a dignity that refused to be broken. He chose to carry water — a humble job, but noble at its core.

In this shift from “professor” to “water carrier,” Masa felt no humiliation. On the contrary, he saw a moral continuity between the profession he left behind and the one that now carried him. “Both come from the same source,” he said, “a sincere desire to serve people, to respond to their needs, to be among them and with them.”

As he walked through alleyways, he became a living witness to the tragedy. He heard the stories of widows who had lost their husbands in battle, saw children searching for milk that can’t be made on the frontlines. These stories, he says, enriched his professional soul beyond measure. “When you live among people, your words carry more weight. Writing becomes a responsibility.”

For Masa, this new role is a rediscovery of the self. He finds pride and honor in it. He sees it as ethical — perhaps even as pure as the profession he was forced to leave.

Yet deep inside, he still longs to return to his pen. He takes notes, collects stories, rewrites sentences in his head as he fills barrels of water. He awaits the day peace returns to the country — and with it, the word.

“I’ll come back,” he says, “carrying stories written by my feet on scorched earth, and heard by my ears in the heart of thirst.”

In a country where survival has become a profession, Khalid Masa remains a living lesson in resilience, in persistence, and in the truth that professionalism isn’t just what’s printed on your ID card — it’s what you build, day by day, in your conscience.

Masa says: In Khartoum, a city once bustling with newspapers and printing presses, journalism has become a suspicion. Paper no longer holds words, and screens can no longer carry voices. War, in all its brutal nakedness, took us all by surprise. But for journalists, its impact was like a bullet that never misses the heart: the profession lost its meaning, becoming a heavy burden — and at times, a threat to one’s very life.

He continues: More than a decade ago, I chose journalism not just as a profession, but as an identity. I received my first professional license in 2011, though my involvement in the field began much earlier. Since the early 2000s, I’ve been active on forums like “Sudanese Online,” writing, commenting, and cultivating a professional ethic that extended far beyond print.

I moved between politics, sports, and human rights. I hosted programs on television, wrote for daily newspapers, and spoke in the voice of a generation trying to redefine its role in a homeland that’s hard to understand — and even harder to abandon.

Over time, “journalism” became inseparable from who I was. When my name was introduced, the word always came first: “journalist.” It felt like a family name I couldn’t escape, even as journalism turned into a battlefield.

In April 2023, when the first shot rang out in Khartoum, I was there. I wasn’t chasing a scoop — I was seeking clarity about what was happening around me. Suddenly, there was no time for questions. The camera became an accusation, the notebook an incriminating document, and professional affiliation a dangerous liability.

The city that cradled my beginnings had become a geographic trap. The journalist who now leaves home in disguise, writes in secret, and edits each word ten times before publishing, knows that the “profession” he once chose freely had become a prison he could no longer escape.

The institutions collapsed, printing presses went silent, colleagues fled, were arrested, or disappeared into the shadows. Every attempt to keep working felt like stepping across a bridge made of fire. Yet deep inside, there was a persistent voice: How can I give up my voice now — after everything this profession taught me about how to look people in the eye and bear witness to their truth?

The dilemma wasn’t only about security — it was economic too. How do you survive from a profession that’s now practically banned? How do you earn from words now considered a threat — erased by censors or bullets? And while a few international platforms still offer support to Sudanese journalists, working with them from a besieged Khartoum feels like leaping through the air without a parachute.

The war changed everything — but it didn’t change what was inscribed deep inside me: that this profession, despite all its pain, is more than just a job. It’s a choice, a commitment, and a personal narrative that cannot be erased from one’s identity.

In a country ravaged by chaos, where truth is stolen from the mouths of its people, I still believe journalism — fragile as it is — remains one of the last attempts to make sense of this ruin, even if only through one shadow-written word.

In an era where values collapse and personal dignity splinters, I found myself forced to shift professional identities. It wasn’t an easy decision, nor a gentle transformation. It felt more like silently shedding a skin — one formed through sweat, writing, and moral conviction.

I was journalism, and journalism was me. But when war erupted, it took from us the luxury of profession — even the space to dream. The very conditions of life were rewritten, and with them, our priorities shifted: securing a day’s food became more urgent than writing a column. Survival mattered more than scooping a story.

I chose a new trade — simpler, more aligned with reality, and less exposed to danger. Outwardly, it lacked journalism’s prestige and sparkle. But at its core, it offered me a different kind of dignity. Despite scarce resources and limited opportunities, this job gave me a financial lifeline for my family — without begging or losing self-respect.

I never felt ashamed of it. I never glorified it — but I never disrespected it. It wasn’t a diminishment of myself, but a way of holding on to something within me. I did the work professionally, building a new layer of awareness within — one capable of noticing small details amid the chaos of daily survival.

Though my new identity is different from the one I carried for years, it has preserved a sense of internal consistency — keeping me in close contact with people, their needs, and their everyday struggles.

This experience placed me among the people — not above them. It pushed me to understand life from a different angle, to listen to people’s worries at the market rather than in a newsroom. And from there, stories began to gather in my mind — raw material waiting for the day when the journalistic climate is restored, and the voice returns to full volume.

It is not a loss to change your profession during wartime. It might even become a new reservoir of experience and perspective — enriching you when you return to your first calling.

Professional decline doesn’t begin with changing jobs — it begins when you despise the one you’ve chosen. And I never despised this shift. I saw in it a moment of necessity, of survival — and of dignity.

Journalism will return. And I will return to it — carrying with me a deeper experience, a wider vision, and a treasure trove of stories that can only be told once the embers of war cool down.