How are Sudanese war refugees facing atrocities in Libya?

Source: infomigrants.net

Since the outbreak of conflict in Sudan in 2023, more than 240,000 Sudanese refugees have arrived in Libya. There, Sudanese refugees face a tragic fate, experiencing rape, murder, and organ harvesting. This has left some waiting for an opportunity to reach Europe.

Famine, rape, murder, slavery, and organ harvesting are some of the horrors recounted by Sudanese who fled to Libya after the outbreak of conflict in their country in April 2023. Thousands have been killed since the war between government forces and the Rapid Support Forces began two years ago, according to a Reuters report published on March 13, 2023.

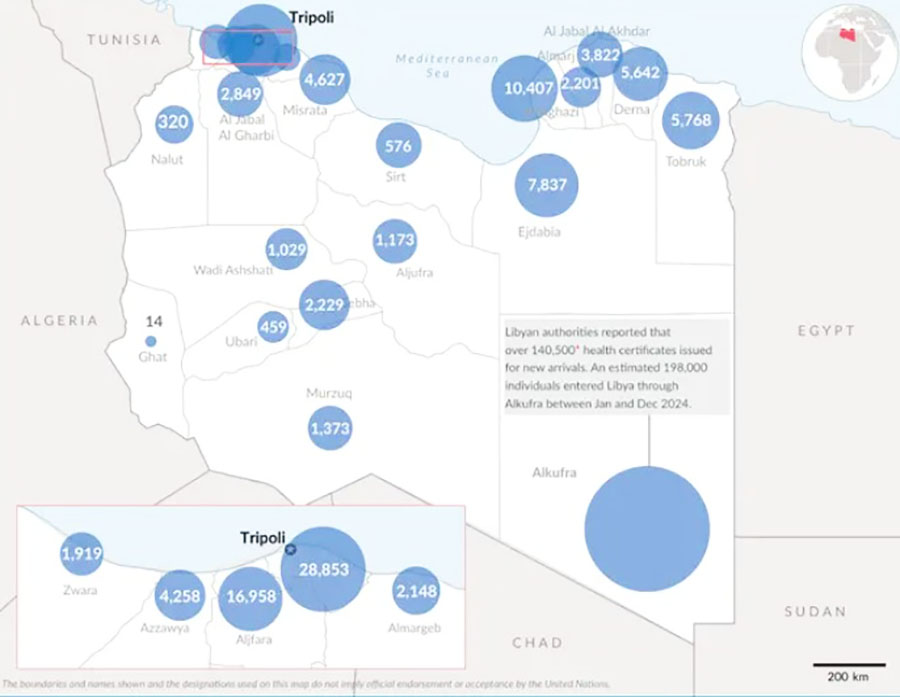

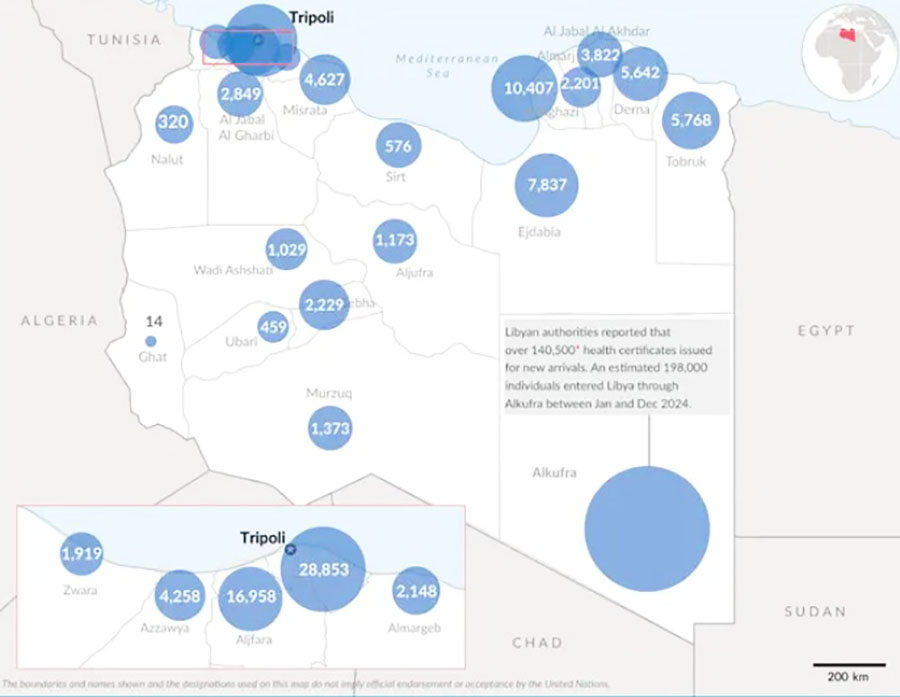

An estimated 12 million Sudanese have been displaced by the conflict, with the majority internally displaced within the country, while more than 240,000 have fled to Libya, and others have sought refuge in neighboring countries such as South Sudan and Chad, according to a February 2023 UNHCR report.

Tragedies of the Journey

Speaking to Reuters, Farid (name changed), a 17-year-old Sudanese refugee from El Fasher in North Darfur state, revealed some of the horrors he witnessed in Libya during his journey. Farid recalled passing through Kufra in southeastern Libya, an area that has recently made headlines for its gross human rights violations. A few weeks ago, mass graves containing the bodies of dozens of migrants were discovered near the city.

Many Lose Their Lives

Farid told Reuters that his situation is similar to that of hundreds of Sudanese war refugees. They seek help from Libyan authorities but dont receive what they expected. Instead, he has witnessed deliberate starvation by criminal tribal gangs in the area. He noted that "many are dying in El Fasher from hunger," asserting that warring tribal factions are stealing and selling international food aid.

Farid explained that he witnessed not only deaths from starvation, but also brutal murders. “I saw a girl being beaten and raped, then killed, and her body left in the street,” he said. “The mother brought her body back to Sudan, preferring to die in the war rather than remain in Libya.”

Organ Stealing in the Desert

Farid, a Sudanese refugee, recounted his horrific experience in the Libyan city of Kufra, where he was forced to sleep in the open and suffered severe hunger before receiving a mattress and some food from the Libyan authorities. Despite this, he continued to suffer, forced to work long hours collecting plastic waste for recycling without receiving any pay. Farid noted that when he complained to officials, they threatened that if he caused any problems, he would be sold to one of the rival militias in the area.

Farid told Reuters: “Kufra is a tribal area, and we are just slaves in their land. They force us to fight for them or sell us into forced labor. If you refuse, they can take your organs and bury you on the road.”

According to a 2021 report by the British firm Grey Analytics, criminal gangs in Libya are active in the organ trade, particularly targeting Black African migrants. Victims are sold into slavery and then their organs are harvested. This network includes brokers, doctors, hospitals, and shipping companies. The stolen organs are sent to countries in the Arab world, as well as to Israel, the United States, Canada, and Europe, according to the Grey Analytics report.

The Sea Won’t Hurt You

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Sudanese refugees in Libya make up about three-quarters of the country’s total refugee population, with hundreds arriving daily and dozens believed to be dying in mysterious circumstances.

Farid eventually managed to escape the brutality of Libya’s desert regions and continued his journey to the north of the country, where he boarded a boat bound for Europe.

A Snakes and Ladders Adventure

Ahmed, a 19-year-old Sudanese man (not his real name), described his arduous journey through Libyan prisons as a game of "snakes and ladders." His journey began in detention centers stretching from Kufra in the south to Zawiya and Ain Zara in the north. Each time he was arrested, he was forced to pay money to be released. If he was arrested again, he had to start all over again, as if he were back at square one in the game of "snakes and ladders."

Ahmed said his journey across the Mediterranean was like a "lottery in a small boat," with the type of boat migrants were allowed to board varying based on their ability to pay. Egyptians and Syrians often had the means to pay for the journey, giving them a chance to cross in safer boats. Sudanese and Eritreans, on the other hand, struggled to secure the money, reducing their chances of a successful crossing on safe boats.

Ahmed noted that the cost of some crossings can reach 15,000 (approximately €13,790). Despite having died several times, especially at sea, he said he was willing to risk his life again, saying, "Dying at sea is better than dying in Libya. The sea will not torture you." Like many other migrants, Ahmeds journey ended in Italy, beginning a new chapter in his ordeal in search of safety.