Wasted Childhood in the Cruelty of War

Special Report – moaatinoun

The lack of social studies on the 2003 Darfur war—combined with academic and cultural detachment in Khartoum’s elite circles—has led to a failure to shed light on the grave violations against children. This neglect resulted in a lack of education, healthcare, and opportunities for a dignified life and a bright future, ultimately contributing to the resurgence of war in 2023.

Most of the soldiers in the current conflict were children during the Darfur war, according to thinkers and experts who spoke to Atar. They emphasized that these children grew up with vivid memories of bloodshed, killings, war narratives, and a culture of revenge. However, they were never reintegrated into a culture of peace and tolerance, nor were their social and psychological conditions addressed. The wealth of their region was not utilized to secure a better future for them, while global media exposure and a strong sense of solidarity with issues related to the central governments ambitions to dominate resources further fueled their grievances.

Additionally, the widespread availability of weapons and early training of children in their use meant that, after two decades, the crisis remained unresolved. The children of the past war have now taken up arms, addressing the conflict through violent means on a much larger scale, covering about 70% of Sudans territory. This is further compounded by new regional and ideological interests that have emerged.

Harsh Beginnings in Exile

Renowned thinker Mohamed Abdel Rahman "Bob" highlights two key issues regarding the lack of social studies on armed conflicts in Sudan, particularly the Darfur war. Speaking to Atar, he argues that beyond theoretical discourse, there is a need to break away from the cycle of humanitarian organizations, refugee camps, and aid dependency.

He draws a parallel with the southern Sudan war and the Darfur conflict, both of which have continuously fueled new generations of war. He cites the Anya-Nya wars of the 1960s, which laid the foundation for the Sudan Peoples Liberation Army (SPLA) in the 1980s. "Children who grow up in conflict zones become the fuel for future wars," he warns.

Abdel Rahman also references the Eritrean liberation war and Somalia’s Islamist youth movements, stressing the dangers of children becoming victims of violence or armed conflict. He criticizes the role of humanitarian organizations, arguing that removing children from their natural social environment and traditional upbringing isolates them from society, denying them formal education.

"Keeping children in exile and refugee camps fosters an entirely different memory," he explains, emphasizing that social studies—not political narratives—are needed to truly understand their experiences. "It is this lack of integration that brings war back every twenty years."

According to him, depending on humanitarian aid solutions creates a generation that is disconnected, deprived of rights, and excluded from political influence. "They have no political system to protect them, and this is exactly what happened in Darfur, the Nuba Mountains, and across the Horn of Africa, where children became the primary resource for fueling prolonged wars."

He sees no immediate solution, lamenting the absence of organized social forces and the military’s reluctance to engage in peace efforts. "The longer the conflict lasts, the more displaced communities become convinced that rebuilding their societies is impossible." He warns: "The catastrophe is that we are failing to recognize that entire generations are growing up in exile."

"How do you erase the collective memory of destruction from a child’s mind?" he asks, stressing that peaceful solutions become impossible for children who have never known anything but violence.

Playing with Childhood’s Paradise

The 2010 Sudanese Child Act unequivocally defends childrens right to life and development. It states that protecting the child’s best interests should be the priority in all decisions, regardless of which authority makes them.

"Dont our children have the right to live, grow, and thrive in peace?" asks child rights expert Yasser Salim. "How can we guarantee childrens right to survival if we don’t demand an end to war and its catastrophic impact on them?" Speaking to Atar, he stresses: "Children must come first in all matters."

Salim highlights that the Child Act overrides any contradictory laws, ensuring protection from all forms of violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The law mandates psychological and social reintegration for child victims of war.

However, he questions whether such protections are possible without actively advocating for an end to the war.

According to UNICEF, 1.6 million displaced children in Sudan require urgent assistance, including those in conflict-affected areas. Children constitute 61% of internally displaced persons in camps and 65% of refugees. Many have suffered trauma before and during their displacement, making them even more vulnerable to abuse, exploitation, and violence.

The statistics are staggering:

2.3 million children suffer from malnutrition, with severe acute malnutrition affecting 694,000 children.

11 out of 18 states have malnutrition rates exceeding 15%, surpassing the emergency threshold set by the World Health Organization (WHO).

820,000 children under five lack access to basic healthcare and vaccinations.

36% of primary healthcare facilities in Sudan are completely non-functional due to staff shortages or damaged infrastructure.

"The impact of war on children is undeniable," Salim asserts. "We are witnessing one of the worlds worst displacement, education, and health crises." He warns that Sudanese children are haunted by war, floods, disease, and famine, which directly violates the international principles of child protection.

"There is no option but to call for an end to the war," he states. "The best interest of the child, as outlined in international conventions, demands it."

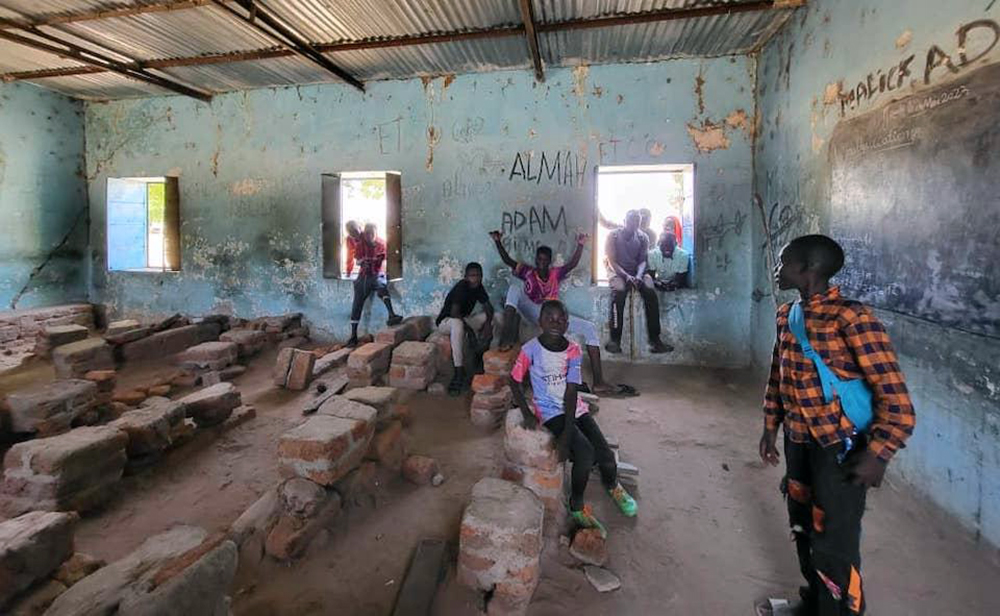

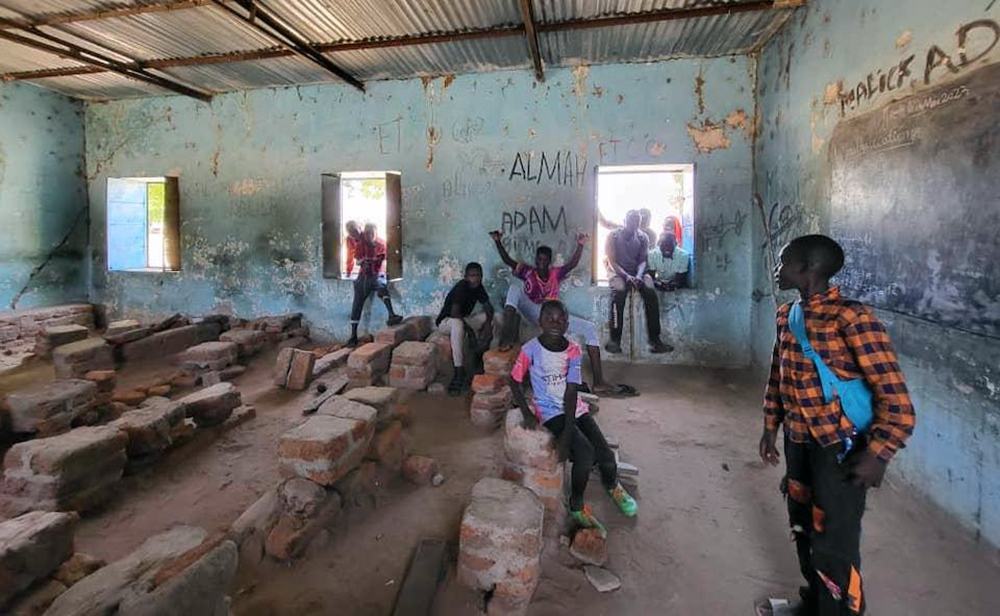

Terrorizing Innocence: The Spread of Weapons

Children make up half of Sudans total population of 40 million. Over the past two decades, their living conditions have improved, with a decrease in infant mortality rates and an increase in primary school enrollment. The country has also remained polio-free due to high vaccination coverage. However, according to UNICEF, millions of children still suffer from ongoing conflict, seasonal natural disasters, the spread of diseases, and a lack of investment in essential social services. Sudan is currently ranked among the worst countries in the world for malnutrition, with three million school-aged children out of school.

Ten-year-old Mohamed eagerly awaits the end of the school year to return to work at "Abour Shendi," selling ice cream and chasing long-distance buses to sell sandwiches and biscuits to passengers. He earns about ten Sudanese pounds per day. "We often board the buses to sell at upcoming stops and return on another bus at the end of the day," he tells "Atr."

Mohamed and his parents were displaced from Omdurman, finding themselves in a new social environment where child labor is accepted and even encouraged at an early age. Despite excelling in school, Mohamed was drawn into buying and selling to support his family, though he has not yet dropped out. His future in education, however, remains uncertain. Many children in the village he relocated to leave school each morning in search of livelihood, often never returning to their studies. The social pressure is strong, and Mohamed finds himself imitating them, especially since his mother also took up selling goods to support his father in the face of displacement hardships.

Similarly, 13-year-old Rayan helps her mother sell food in Shendis Deim market, where her mother rents a small kiosk that serves as both a restaurant and a shelter throughout the day. Rayan, her mother, and her sisters fled from "Al-Nakheel" neighborhood in Omdurman after intense fighting broke out. Her education has been on hold for two years, and she now spends her days taking orders, washing dishes, and helping customers. Her mother watches over her closely to protect her from harassment, a recurring issue. "I had two choices: continue my studies and add to my mother’s burdens, or help her with work. I chose to help her and sacrifice school without hesitation," Rayan tells "Atr."

War disrupts childrens basic needs—food, water, shelter, healthcare, and education—hindering their physical, social, emotional, and psychological development. In war zones, child labor becomes a necessity for survival, and many are forcibly recruited as child soldiers. Estimates suggest that there are around 300,000 child soldiers worldwide, 40% of whom are girls, all victims of armed conflict. These children are forced to leave their homes, suffer from sexually transmitted diseases, and endure the horrors of war.

The April war has inflicted immense psychological damage on Sudanese children. Graphic images of atrocities, looting, and human rights violations flood social media daily. Armed mobilization in neighborhoods and the normalization of weapon carrying have left children exposed to relentless violence without protective barriers to shield them from its brutal reality. Without interventions such as studies and programs addressing the psychological and humanitarian crisis among children, they risk becoming future recruits for war. Psychological support plays a crucial role in rebuilding lives, enhancing resilience, and fostering sustainable recovery in the aftermath of conflict and displacement.

Speaking to "Atr," academic and social specialist Mubarak Maman explains: "Displacement due to war significantly affects children. Social and psychological support is vital to help them process their experiences, overcome challenges, and build a foundation for healthy growth. It also helps remove psychological barriers that hinder integration and reintegration, making their transition smoother."

Psychological support not only aids adaptation but also reduces the stigma associated with mental health challenges, encouraging displaced individuals—whether returning to their home countries or integrating into new communities—to seek the help they need. "This enables them to face ongoing challenges and uncertainties with greater strength," Maman adds. He concludes with one final statement: "In short, it requires the collective effort of academics, mental health professionals, and social workers."